Decision Mountain

Jerry Seinfeld used to hang pictures of the Hubble Telescope in the Seinfeld writers room.

Judd Apatow, interviewing Seinfeld for his book on comedians, Sick in the Head, asked why.

“That would calm me when I would start to think that what I was doing was important. You look at some pictures from the Hubble Telescope and you snap out of it.”

Apatow pushed back, saying how depressing that sounded.

“People always say it makes them feel insignificant, but I don’t find being insignificant depressing. I find it uplifting.”

We’ve all been smacked in the face with how insignificant we are and how fleeting this all is the past week. It’s rare that there’s an inflection point that hits the whole country (world). But here we are.

And let me caveat this with the obvious — your first priority is to take care of yourself, your family, your friends. Don’t be a jerk, don’t hoard, etc. But if you’re reading this, you’re probably in a group of people that (I hope) will be fine.

Which means your second priority is to not screw this up.

We’ve been given something pretty unique — space and time for reflection. Permission to change. Context for how unimportant what we do really is.

I’ve gotten a bunch of emails like this one from Josh this week:

I think what Josh’s approach makes sense. I talk a lot about the tactics of how to start a startup and evaluate the shift post-corona in the pod.

But I wanted to touch on something that’s been sticking in my mind for a few weeks and bubbling for a few years. And it might be a better answer to the question Josh isn’t asking. There also might not even be a deeper question and I’ve just got cabin fever. Either way, this was therapeutic and fun, so here we go.

Decision Mountain

My Dad was early to Apple products. A big reason he was so drawn to them was that he understood software development. He understood that the operating system for Microsoft was built in the 80s and each new iteration of Office was just new code stacked on top of decades old code. That’s a terrible way to build a product. It slows everything down and limits the type of decisions you can make, because anything new you create needs to play nicely with the older stuff. Apple’s OS was built from scratch. He knew they’d innovate circles around Microsoft.

Corona has given us a unique chance to reflect on our operating system.

Our operating system isn’t made up of code, but decisions. I visualize it as a mountain we all sit on top of. I’ve decided to call it… Decision Mountain.

And because corona is scary and pictures are fun, let’s draw it out. Here you are, on top of all the decisions you’ve made to get to this point.

Each new decision you make is sometimes consciously but far more often subconsciously impacted by all the decisions we’ve made in the past. Just like Microsoft, our potential is being sapped and channeled by legacy decisions.

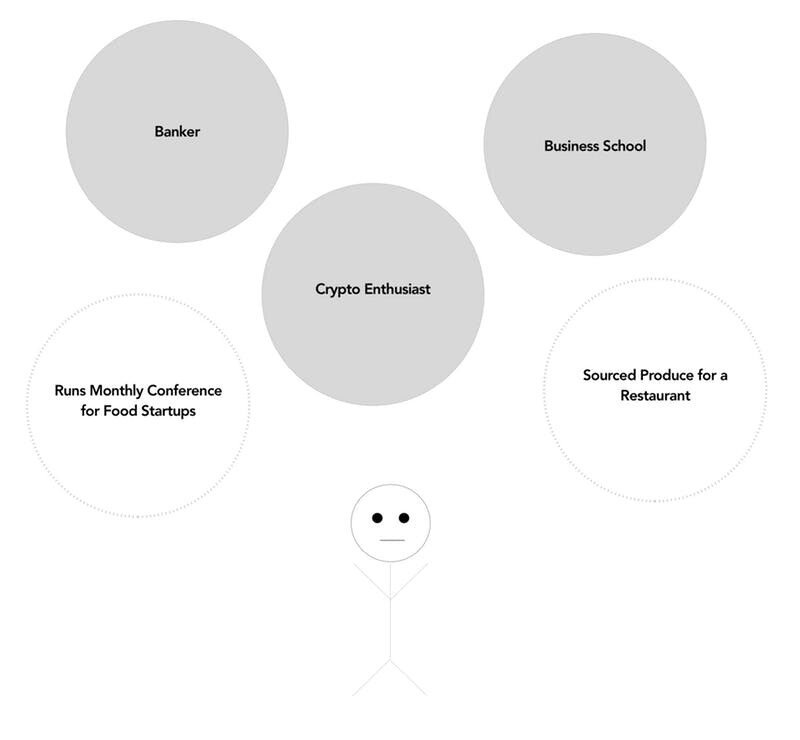

Six months ago, if you’d decided to switch jobs, you’d most likely just look for other companies where you’d be doing basically the same thing. Here’s a project manager leaving Google to try something new.

As you move along in your career, decisions stack up and make your perceived options more and more specialized. In 2020, specialized is very bad — I’ve recommended Range before and I will again.

The view from the top of Decision Mountain causes three things:

Sunk Cost Fallacy. We’ve already been doing project management for 4 years, is it really worth considering something else? All our recent decisions are leading us to more project management.

Short-term + Specificity bias. We underestimate the value of breadth of experience and the benefits of starting from the bottom in a new industry. We think impossibly short-term, ignoring that we’ll probably be working for another 40 years, and wide, unique experience is the biggest differentiator.

The bias of not realizing past you was probably a moron. We tend to overestimate how thoughtfully we made the decisions that led us to this point were.

Let’s look at number three quickly. This is a painful exercise I’d recommend everyone do now that you’ve got some time.

I went to business school at age 24. I decided to go because I hated my current job in finance, and a few people had told me business school was a great way to “keep your career moving forward” while still figuring out what you wanted to do.

The other option I thought hard about was becoming a writer. I loved writing. But I was 24. It was way too late to make that sort of drastic career change — I legitimately remember thinking this. And how does one get into writing anyway?

Business school it was.

That random calculation nearly dictated every decision I made until I was 65 and retired. For about 95% of my classmates, it has. Once you go to business school, you’re primed for banking, consulting, or brand management. You then move to NY, Boston, SF, or whatever city your b-school was nearest to. You marry certain types of people and you’re friends with certain types of people. The lifestyle (cost) and decisions (status) reinforce themselves, and that’s your career. That’s your life.

Which is great, if that’s what you want. But let’s explore why was I in finance in the first place.

Here’s where it gets ugly.

I’d gotten into finance because I’d been an economics major and my friend got me an interview and told me how to ace it.

Ok… well why was I an econ major?

Because 18 year-old Brian thought econ sounded like the second most “serious” major behind engineering, which is what I wanted to major in but couldn’t because the labs conflicted with basketball practice.

Also, econ classes all met after 1pm.

So, to recap, I nearly set my entire life on a certain trajectory that started because I wanted to have a serious sounding major and not wake up before noon when I was 18.

These stacked decisions push us down a specific path as we make decisions semi-consciously.

The biggest problem with this type of path?

Everyone starts to look the same.

“What the f*ck am I doing with my life?!”

That’s the other email I’ve gotten a bunch this week. It turns out corona is an effective mirror for a lot of people.

As I interview more founders for Idea to Startup, it’s become strikingly clear what actually primes someone to be a successful founder: a unique perspective. You certainly need grit and luck and timing and a big market and all that — but that’s table stakes and we knew that and we can evaluate and teach and navigate through that.

The real differentiator is just having a bunch of experiences which lead to a perspective other people can’t possibly have.

Maybe you’ve been a social worker for 10 years then start a bakery. Maybe you’re in business school and are amazed by the new SaaS business model then you start a video game. Just about every interview I’ve done has the intersection of a weird ven diagram of experience or knowledge.

Interesting things are never started by people who sit way up top on a narrow decision mountain. Interesting things are started by people who’s decision mountain has a bunch of separate peaks. They’ve gone deep in an industry for a few years, then bounced to a totally separate one. They spend time figuring out what they are capital-G Great at and double, triple, quadruple down on that through the lens of different industries. They don’t stay on one path because that’s what they’ve done for a few years. They pack their bags and leave. They aren’t in a rush to walk a straight line. They only connect the dots backwards.

So many founders I’ve interviewed took something that was table stakes in one industry and ported it into another where it was earth shattering.

Immigrants are great founders for lots of reasons, but one giant one is they come with at least two core perspectives in a world where most people have one.

So what’s my advice for this forced control-alt-delete? Diversify.

Figure out how you can add some perspective. Add unique circles to your ven diagram so you don’t look like anyone else. Our brains are super smart. They’ll make the connections. We just need to give them access to as many diverse inputs as possible.

And while you’re doing that, look out for what you’re capital-G Great at. You’ll need to lean into that, with a unique perspective, to really make a ruckus (tm Seth).

Final thoughts:

Build a system — We’re all resetting our systems as we work from home indefinitely. Build in time to read, listen, interview people in new industries. The constructs of home / commute / office / gym / restaurant are gone — we need to create barriers. Maybe make yourself OKRs.

Be bold — I obviously can’t tell you to go work at McDonalds if you want to start a food startup but you’ve been in finance the past 10 years. Maybe you have a baseline income. Maybe you’ve got kids to feed. There are different ways to learn the restaurant industry. But be honest with yourself — if your life depends on learning Mandarin, you probably won’t just buy Rosetta stone. Figure out ways to truly immerse yourself and understand that perspective.

Random — Stop reading the news. Three times / day max. You’re quarantined. If something really important happens someone will reach out directly. We don’t need Ja Rule at a time like this (nsfw but everyone’s home so probably fine but earmuff the kids).